Vincent Gramoli

School of Computer Science

1, Cleveland St.,

NSW 2006 Sydney

Follow @VincentGramoli

Leaderless Consensus

13 Feb 2026 - Vincent

Recently, I have been asked what a leaderless consensus protocol is. This notion has been so instrumental to ensure scalability of blockchains that it is important to explain it here.

Leader-based consensus protocols

Since 1999, with the influence of the beautiful Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerant (PBFT) consensus protocol [1], most consensus protocols designed to cope with unexpected message delays and Byzantine failures had a leader. They were often variants of the PBFT consensus protocol, this is why so many blockchains built upon leader-based consensus protocols, like Tendermint, Concord, Quorum, Aptos, Diem… to name a few.

Practicality with four LAN nodes

For at least the past 16 years, researchers knew that leaders were creating bottlenecks [2], this was also explained in this previous blog post. However, the leader abstraction was well known to break the symmetry needed for all correct nodes to converge to a common decision, especially in a network where messages could take longer than expected to arrive. With PBFT, this abstraction even proved practical to achieve good performance in a local area network (LAN) of four machines or nodes. The problem arose when trying with more nodes and in a wide area network (WAN).

The bottleneck effect

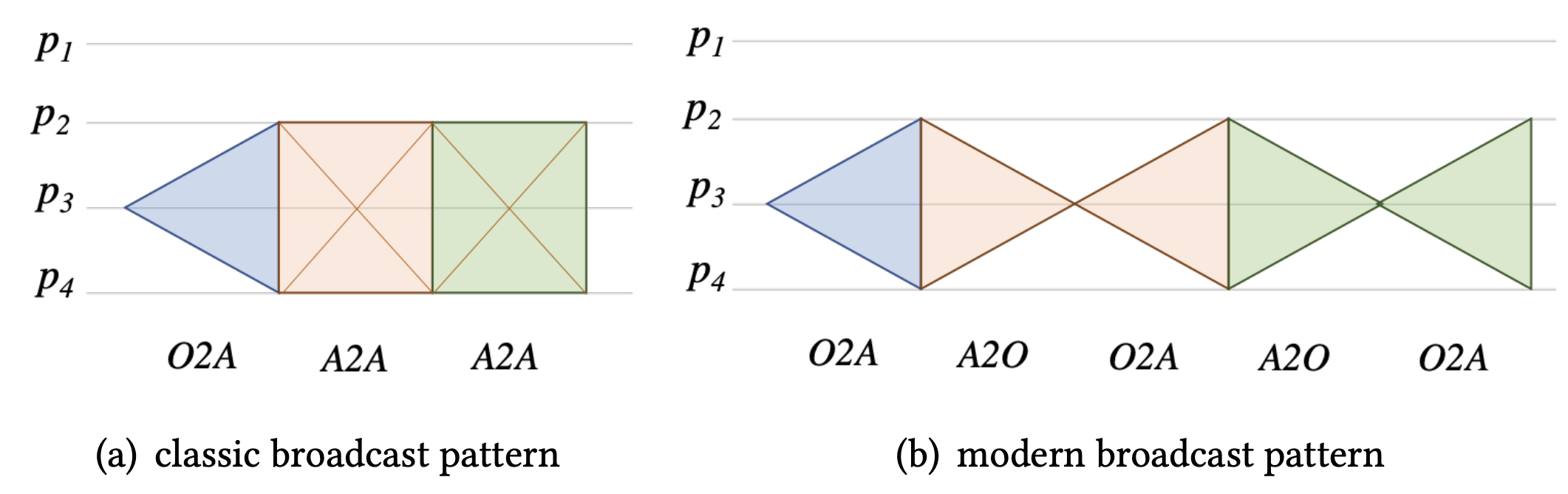

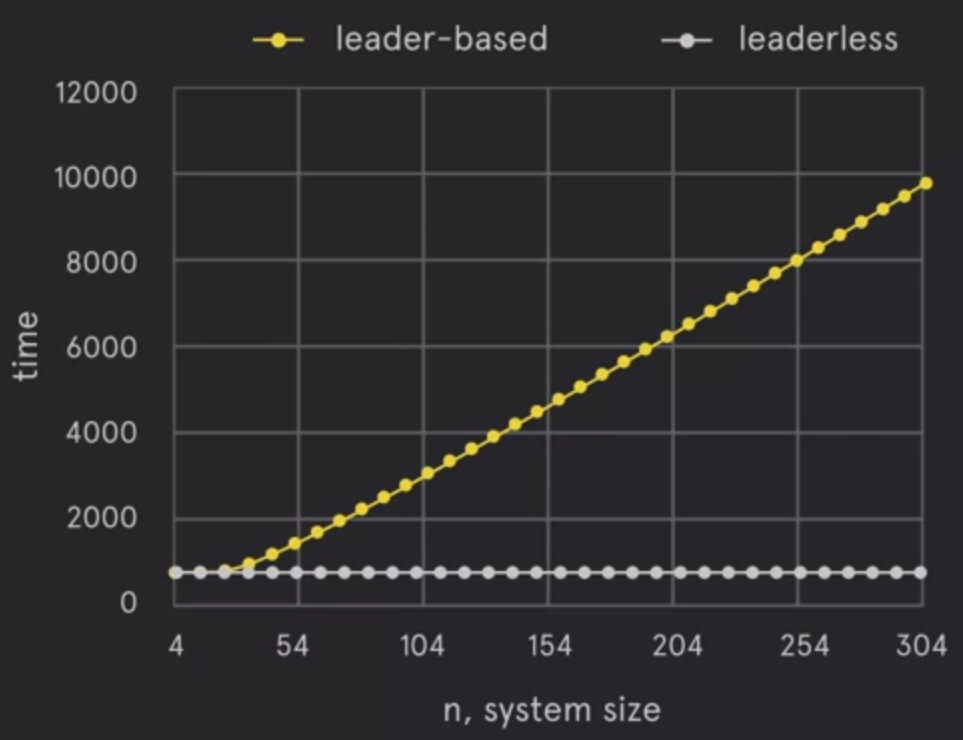

In a leader-based context, the leader would typically send some data item (be it a block or a general value) to everyone in order for them to agree on it. In a WAN, where the broadcast primitive does not exist at the IP layer, the leader has to send repeatedly the same information to different recipients. Therefore, when the number of nodes grow, so does the amount of data the leader has to send. The network interface of the leader then becomes the bottleneck. Although they are alternatives that try to minimize this bottleneck effect where the leader does not send all the data to everyone, it just delays the bottleneck observation to when more nodes participate. As one can see on this graph taken from [7], leader-based protocols send to all other nodes, which then either exchange among themselves or respond back to the leader.

Bittorrent-like dissemination

With the advent of peer-to-peer systems in the 2000s, new communication patterns were proved instrumental to share a file fast by bypassing the bottleneck effect of a single sender. The idea was to share a file in a large network by splitting it in a series of chunks, such that multiple nodes would contribute to sending distinct chunks to the recipient. By having multiple nodes sending smaller chunks, the recipient would obtain the file with all chunks faster than if all its chunks were sent by the same sender.

A Collaborative Communication Pattern

Redbelly [3] made an interesting observation that blocks could be combined into superblocks rather than deciding upon a single block proposed by a single node (e.g., leader). The idea was to leverage the blocks proposed by multiple nodes rather than deciding only one of them and rejecting the others. This led the throughput to scale with the number of nodes, by accepting potentially as many proposed transactions as the number of nodes that would propose transactions. This led the latency to scale as well by benefiting from the Bittorrent idea: the recipients would receive the data faster.

Leader-freedom

This concept was implemented on top of the Democratic BFT (DBFT) consensus algorithm [4] that was later formally proven correct for any system size with parameterized model checking [8]. Its name “Democratic” stems from its leaderless design letting it converge to an agreement despite any single node acting arbitrarily. A formal but slightly stricter definition [6], which received the Best Paper Award of ICDCS’21 [5], required that any execution would converge regardless of the behaviour of any single node. Although theoretically interesting, we are not aware of an implementation that would be as efficient as DBFT.

Conclusions

The design of consensus protocols has evolved considerably over the last decades. While the leader-based design has proved practical in a local area network for few machines to agree with one another, the leaderless design has now proved key for blockchains to scale to a wide area network. To this end, it alleviates the leader bottleneck, leverages the bandwidth of disjoint communication channels and offers a collaborative approach that leverages nodes resources.

[1] Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance. Miguel Castro and Barbara Liskov. OSDI 1999.

[2] A leader-free Byzantine consensus algorithm. Fatemeh Borran and André Schiper. In Distributed Computing and Networking, pages 67–78, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2010. Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

[3] Red Belly: A secure, fair and scalable open blockchain. T Crain, C Natoli, V Gramoli. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S&P), 466-483, 2021.

[4] DBFT: Efficient Leaderless Byzantine Consensus and its Application to Blockchains. T. Crain, V. Gramoli, M. Larrea and M. Raynal. In 2018 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Network Computing and Applications (NCA), 2018.

[5] Leaderless Consensus. K. Antoniadis, A. Desjardins, V. Gramoli, R. Guerraoui, I. Zablotchi. IEEE 41st International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), 392-402, 2021, Best Paper Award.

[6] Leaderless Consensus. K. Antoniadis, J. Benhaim, A. Desjardins, P. Elias, V. Gramoli, R. Guerraoui, G. Voron, I. Zablotchi. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing, 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.jpdc.2023.01.009.

[7] Planetary Scale Byzantine Consensus. G. Voron, V. Gramoli. ACM Workshop on Advanced tools, programming languages, and PLatforms for Implementing and Evaluating algorithms for Distributed systems (ApPLIED), 2023.

[8] Holistic Verification of Blockchain Consensus. N. Bertrand, V. Gramoli, M. Lazić, I. Konnov, P. Tholoniat, J. Widder. 36th International Symposium on Distributed Computing (DISC), 2022.