Vincent Gramoli

School of Computer Science

1, Cleveland St.,

NSW 2006 Sydney

Follow @VincentGramoli

Blockchain Can Finally Tolerate Colluding Majority

23 Apr 2024 - Vincent

We found a blockchain protocol, called ZLB [1], to cope with a coalition of any size. Before that, adversaries controlling the majority of the resources could break any blockchain network. This has been dramatic, as we are aware of many millions of dollars that got lost or stolen due to this problem. The key to bypass this limitation relies on solving the accountable consensus problem: either reaching consensus because the coalition does not lie sufficiently to other nodes, or producing undeniable proofs of fraud to ban liars from executing further consensus instances. The amount of applications of ZLB is vast and its performance is close to the best performing blockchains. Update: this scientific publication [1] has just received a Best Paper Award from the 54th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks.

Until now, blockchains were doomed to fail if a majority of the participants were misbehaving. The reason is intuitive: if an adversary controls more resources than the rest of the system, then it can presumably rewrite the history of the blockchain. The 51% attacks illustrates this problem in Proof-of-Work blockchains where an adversary owns more than half of the mining power of the network. But this problem also applies to Proof-of-Stake blockchains where the adversary controlling more stake than the rest of the network can outvote anyone. This is a major problem considering the natural tendency for the distribution of resources to be skewed as we explained in a previous block post.

One may say that tolerating a minority of failures is not too bad, given that researchers know that it is impossible to reach a consensus on a unique block as soon as the adversary controls 1/3 of the network. The drawback if that these blockchains cannot guarantee that consensus is reached. Forks happen due to disagreements and best efforts strategies are employed to prune branches and converge back into a chain. This has led people to lose $18M in Bitcoin Gold and $5.6M in Ethereum Classic. This is dramatic as it limits, rightfully, the adoption of the largest blockchain protocols for trading large value assets like real-world assets, assets we cannot afford to lose.

We have just discovered the first blockchain that tolerates a majority of failures. The key to bypass the limitations of existing blockchains is to exploit accountability, a recent concept to hold misbehaving participants responsible for their actions and to observe that blockchains incentivize nodes to be active, either contributing rewards to their owner or trying to steal assets. The problem we solved is far from being easy for two reasons. First and due to the CAP theorem [2], if a majority of the network is inactive, then the blockchain is useless because unavailable or inconsistent. Second, if the adversary controls a majority of resources it can produce disagreements by convincing two parts of the network about different legitimate blocks in which two transactions double spend.

Our solution, called the Zero-Loss Blockchain (ZLB), is a blockchain that first executes the formally verified blockchain consensus DBFT [3], but with accountability built in, similar to Polygraph [4] that identifies any liar during the consensus execution. If an overwhelmingly large coalition manages to produce a fork in the chain by lying to different correct nodes, then ZLB detects them and forbids them from participating in the consensus. This process weakens the coalition until it is not large enough to convince correct nodes of a disagreement. The fact that this protocol is provably correct stems from the simple observation that nodes have to lie to create a disagreement.

So why is this blockchain called ZLB? It actually allowed us to implement a zero-loss payment application on top of it. The application requires nodes to stake more coins than they are allowed to transfer in one block. If a coalition misbehaves and produces a fork, then ZLB generates an undeniable proof-of-fraud identifying the guilty nodes responsible of the attack. The conflicting blocks at the same index get merged by picking one payment and reimbursing any conflicting payments with the assets staked by the guilty nodes. This is just one illustration of what the ZLB blockchain offers by tolerating colluding majorities.

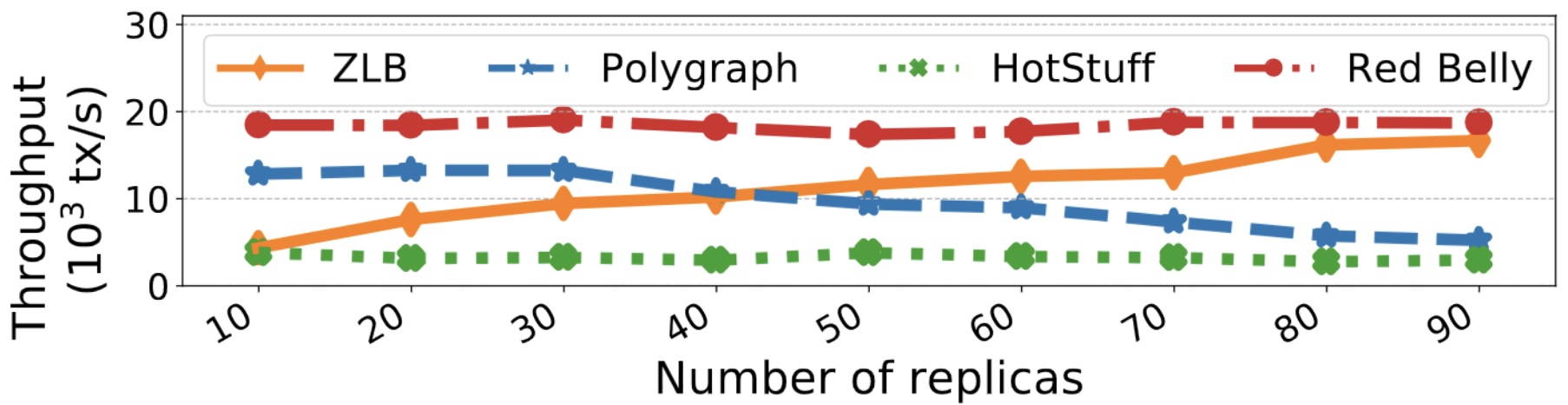

Finally, we also evaluated the performance of our ZLB blockchain that achieved close to 17K TPS in a geo-distributed network as indicated in the figure above. As a result, ZLB outpeforms the raw HotStuff [5] consensus protocol by 5.6 times, which indicates that ZLB would also outperform any HotStuff-based blockchain that would have to validate and execute transactions in addition to running HotStuff. Finally, we noticed something remarkable when running coalition attacks against our network. As the system enlarges, so does the latency of messages between blockchain nodes, which reduces the effects of lying because the lies get detected before they can even cause forks. As the performance of ZLB increases as the system size increases, we noticed that it performs similarly to the Redbelly blockchain [6] at large scale.

A copy of this blog post is available on Medium.

[1] A. Ranchal Pedrosa and V. Gramoli. ZLB: A Blockchain to Tolerate Colluding Majorities. IEEE/IFIP DSN, 2024, Best Paper Award.

[2] S. Gilbert and N. Lynch. Perspectives on the CAP theorem. Computer, 45(2):30–36, 2012.

[3] N. Bertrand, V. Gramoli, I. Konnov, M. Lazic, P. Tholoniat, and J. Widder. Holistic verification of blockchain consensus. In C. Scheideler, editor, DISC, volume 246 of LIPIcs, pages 10:1–10:24, 2022.

[4] P. Civit, S. Gilbert, and V. Gramoli. Polygraph: Accountable byzantine agreement. In IEEE ICDCS, Jul 2021.

[5] M. Yin, D. Malkhi, M. K. Reiter, G. G. Gueta, and I. Abraham. HotStuff: BFT consensus with linearity and responsiveness. In PODC, 2019.

[6] T. Crain, C. Natoli, and V. Gramoli. Red Belly: A secure, fair and scalable open blockchain. In IEEE S&P, 2021.